Criminal Background Checks May Be Banned in N.Y.C. Housing Applications

After she was released from prison in 2011, Kandra Clark spent five years sleeping on friends’ couches while searching for a new home in New York City.

She had a full-time job, but landlords routinely denied Ms. Clark’s rental applications, citing background checks that she believed had flagged her fraud-related conviction. Ms. Clark, 37, who is now an executive at a nonprofit group that helps formerly incarcerated people, eventually found a landlord who accepted her application, in Queens, but the process was “exhausting and defeating,” she said.

Now, New York City is likely to join a number of other cities in limiting the ability of landlords to screen tenants based on their criminal records, which could affect thousands of people seeking housing in the city.

A bill to be introduced in City Council on Thursday would, with a few exceptions, ban landlords and brokers from seeking a person’s criminal records, and bar them from denying housing because of prior arrests or convictions. The mayor has signaled that he is favorable.

Criminal background checks are often a routine part of applying for an apartment in New York City and elsewhere, and advocates for landlords and industry groups maintain the practices are essential.

Nicole Upano, assistant vice president of the National Apartment Association, said that criminal background checks “are a critical element of a rental housing provider’s efforts to keep their apartment communities, residents and staff safe.”

But a growing number of places around the country, including New Jersey, San Francisco and Cook County in Illinois, which encompasses Chicago, have curtailed the ability of landlords to check and screen tenants based on their criminal records.

Such practices place people at risk of homelessness and recidivism, according to politicians and housing advocates, and disproportionately affect Black and Latino communities who are overrepresented in the justice system.

A similar bill did not pass the New York City Council last year, after property owners and landlord groups lobbied against it.

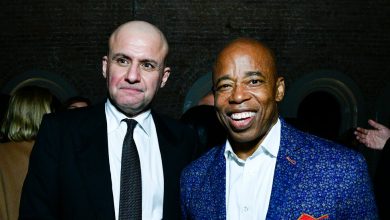

But this year, a new City Council has signaled a more progressive approach toward criminal justice, and the bill already has the support of more than 30 of the 51 City Council members. In a housing plan released this year, Mayor Eric Adams said he would support a bill “creating new anti-discrimination protections for New Yorkers with criminal justice histories.”

A Guide to Renting in New York City

- An Affordability Crisis: Why is it so hard to find an affordable apartment in New York? Here’s a look at the roots of the city’s housing shortage.

- ‘Covid Discounts’ End: Early in the pandemic, landlords slashed rents to attract tenants. Now, more than 40 percent of Manhattan’s available units come from those priced out of apartments they leased during that time.

- Finding Affordable Housing: Use our tool to see which financial programs you may be eligible for and how to apply.

- Rent Regulation: New Yorkers who live in rent-stabilized apartments will see their largest increase in almost a decade. Here’s what to know.

Mr. Adams’s deputy press secretary Charles Kretchmer Lutvak said in a statement:“No one should be denied housing because they were once engaged with the criminal justice system, plain and simple.”

An estimated 750,000 residents of New York City have a criminal conviction, according to the Fair Chance for Housing, a group that has advocated for the bill’s passage. A 2018 report from the Prison Policy Initiative, a nonprofit group that advocates for criminal justice reform, found that formerly incarcerated people are nearly 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public.

The push in New York City comes as public officials have grappled with an uptick in homelessness after the worst of the pandemic, underscoring how the city’s housing crisis has made it increasingly difficult to find an affordable home.

More than 50,000 people were staying in New York City shelters last week, according to a tally compiled by the news site City Limits, and Mr. Adams has made addressing homelessness a main focus of his first year in office.

Keith Powers, a councilman from Manhattan and one of the sponsors on the bill, said he hears daily from New Yorkers who are worried about homelessness and making housing more accessible. “Right here we have a tool that can accomplish that,” he said.

Several states and cities have moved to limit employers from asking about criminal convictions during the initial job screening process in what has become known as the “ban the box” movement.

In 2016, the Obama administration said that private landlords who put blanket bans on renting to people with criminal records — rather than considering each applicant’s criminal record, the nature of the crime and length of time since conviction — may be in violation of federal law. And in April, Marcia L. Fudge, the United States secretary of housing and urban development, directed the department to review its programs and make sure they are “as inclusive as possible of individuals with criminal histories.”

The bill in New York City carves out some exceptions. It would not apply to one- or two-family homes where the property owner also lives. It does not bar landlords from checking whether a prospective tenant is a registered sex offender.

Under the bill, someone who believes they have been discriminated against because of their criminal history could file a lawsuit against a landlord or a complaint with the New York City Commission on Human Rights.

But it is unclear how prepared the city is to enforce the bill’s provisions. It already struggles to enforce a law that prevents housing discrimination against people who depend on rental vouchers.

The bill is likely to draw opposition from some property owners and industry groups.

A spokesman for the Real Estate Board of New York, an industry group for brokers and property owners that had previously opposed a version of the bill, said the group will “review any legislation put forth on this issue.”

Vito Signorile, a vice president at the Rent Stabilization Association, which represents about 25,000 owners, said the group helped defeat the bill last year, in part because tenants in more than 40 council districts had raised concerns about their safety. He said the new council will likely encounter similar resistance.

“Everybody deserves second chances,” he said. “But there has to be a line in terms of who you’re vetting to rent an apartment in your building.”