South Africa’s Highest Court Says Jacob Zuma Can’t Serve in Parliament

South Africa’s highest court on Monday ruled that former President Jacob Zuma was not eligible to serve in Parliament, a decision that may deepen political turmoil in the country just over a week before crucial national elections.

The Constitutional Court, overturning a special electoral court’s earlier decision, ruled that Mr. Zuma could not stand as a candidate in the May 29 election because of a past criminal conviction.

The onetime leader of the African National Congress, Mr. Zuma resigned from the presidency in 2018 amid widespread protests. Three years later, he was convicted and sentenced for failing to appear at a corruption inquiry.

Mr. Zuma’s attempted political comeback has created a big test for South Africa’s fledgling democracy.

He became the first former president to serve prison time in post-apartheid South Africa after his arrest in July 2021, though he was released on medical parole just two months into his 15-month sentence. The Constitutional Court later overturned his medical parole, but Mr. Zuma then received a presidential pardon from his successor-turned-political rival, Mr. Ramaphosa.

The court’s decision hinged on the length of Mr. Zuma’s sentence. While he was granted a remission that reduced his time in prison, he had been sentenced to 15 months, which made him ineligible to run, the court decided.

According to South African law, a person who has been convicted of an offense and sentenced to more than 12 months in prison cannot serve in the National Assembly.

“It is declared that Mr. Zuma was convicted of an offense and sentenced to more than 12 months’ imprisonment,” Justice Leona Theron said.

Mr. Zuma is not “eligible and not qualified” to stand for election until five years after the completion of his sentence, the justice added.

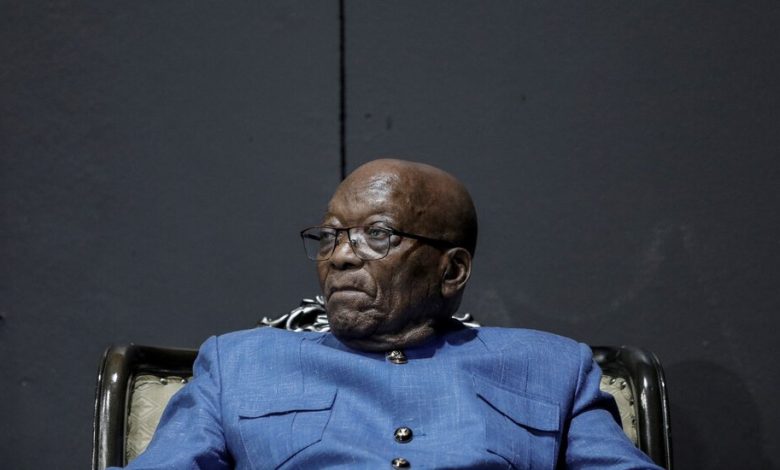

Mr. Zuma, 82, had been hoping to run as the leader of uMkhonto weSizwe, an upstart party founded to challenge the African National Congress, which has governed the country since the end of apartheid three decades ago.

Mr. Zuma’s decision to lead and campaign for an opposition party had deeply unsettled the South African political landscape. Founded in December, uMkhonto weSizwe, or M.K., has quickly become one of the most visible opposition organizations in an election in which a record 52 parties are vying for votes on the national ballot.

South Africans vote for a party instead of an individual, but M.K. appears to be banking on the appeal of a familiar face to attract voters: Mr. Zuma’s photo is all over its campaign posters and T-shirts.

While Mr. Zuma resigned from the presidency in 2018, he remains a popular figure in the South African political landscape, and his populist rhetoric has struck a chord among voters aggrieved with the A.N.C.